- Home

- Mary Jane Myers

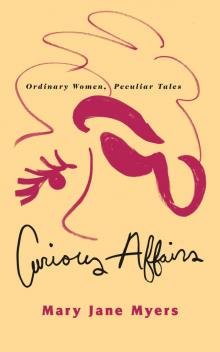

Curious Affairs

Curious Affairs Read online

First Paul Dry Books Edition, 2018

Paul Dry Books, Inc.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

www.pauldrybooks.com

Copyright © 2018 Mary Jane Myers

All rights reserved

A version of “Galileo’s Finger” first appeared in PoemMemoirStory

(Number 12, 2013). Used by permission.

Printed in the United States of America

Print ISBN 978-1-58988-150-1

eBook ISBN 978-1-58988-327-7

For Eva Brann

and Kerry Madden-Lunsford

with gratitude

Warm thanks to my editor

Julia Sippel

for her remarkable intelligence

and understanding

Contents

The Maui Stone

Money Dragons

Galileo’s Finger

The Beautiful Lady

Sappho Resurgent

Beef Medallions

A Day at Versailles

Recovery

The Curious Affair of Helen and Franz

GaGa’s Piano

The Seraphita Sonata

The Carpaccio Dog

The Miracle of the Shellflowers

The Maui Stone

As A TEENAGER, DIANE HATCHER had been a good Catholic girl. In college she stopped going to Mass except at Christmas and Easter, and in the last two decades, had reflexively hidden any overt sign of religiosity. “Oh, I’m not religious, but of course I’m spiritual, you can pray anywhere”—how many times had she repeated that secular platitude at posh parties, angling for the approval of the glitterati. A month before her forty-third birthday, she welcomed in the New Year, 1995, at a beach house in Malibu. Gliding into a crowded room in a pink satin dress that emphasized her size six figure, she scanned her surroundings. A tall and reed slender man flashed a white-veneered smile. A barbered twenty-day beard framed his face, and gold chains gleamed in the v-neck of his purple silk shirt.

“Hello, I’m Mark.”

“Diane. This is a wonderful evening, isn’t it?”

“I ne’er saw true beauty till this night.”

Smirking she said, “That particular romance didn’t end very well.”

He laughed. “Ah, but teenagers are hopelessly stupid. You, I can tell, are bright as well as lovely.”

How ridiculous, thought Diane, even as she enjoyed the slightly sleazy seduction. The room was dimly lit, crowded and noisy. Gloria, an acquaintance from work, was a friend-of-friends of the hosts, and had talked Diane into coming. Gloria was five years older, twice divorced and never a mother (three abortions, she confided, alarming Diane with this offhand sharing). Their avowed purpose at this party was a manhunt, their tactical agreement to separate at the front door.

Gloria had agreed to drive, and picked up Diane at her Santa Monica apartment south of Pico, ten blocks from the ocean. Gloria floored the accelerator of the red Miata, and sped madly north on PCH. Diane scooched down in her seat, looking not at the road, but at the dashboard. She owned a Ford Taurus—safe and boring—and was a little-old-lady driver, used to being honked at by the arrogant owners of Mercedes and Lexus sedans. At least drunk driving wouldn’t be a problem, as Gloria was a “friend of Bill,” with three years sobriety. Diane had forever been a teetotaler.

They left the party together at one in the morning. Diane smelled alcohol on Gloria’s breath, but did not say anything. All the way back, the two prattled about the possibilities. Gloria had given her phone number to three men, one of whom was Mark—the only man to whom Diane had given hers. Diane was relieved when Gloria pulled the Miata up to the curb in front of Diane’s apartment.

At eight o’clock the next morning the telephone rang, Mark’s brassy voice on the line. By the end of their ten-minute conversation, Diane had already surrendered.

Mark was forty-seven, a Jungian therapist whose Century City practice was booked solid with anorexic actresses and the neurotic wives of movie producers. An acrimonious five-year marriage in his twenties had soured him on matrimony. Weekends they spent together at his bachelor digs in the Marina. Every weeknight at eight o’clock he telephoned. The talk was smutty, but not quite telephone sex. She imagined him sprawled on the dark green Morocco leather sofa, dressed in the maroon paisley silk bathrobe she had given him. He held the television remote control in one hand, flipping channels every ten seconds, the mute button set, while he cradled the phone in his other hand. A large photograph of three men was displayed in an acrylic stand on the coffee table. In the middle stood the Dalai Lama in an orange robe, his face as beatific as a Forli angel. On the monk’s right a grinning Mark posed, his characteristic silk shirt open, showing off the dark curls of his chest hair, gold glinting at his neck. On the other side, a somber Richard Gere stared at the camera. She thrilled to this image of Mark, but a matriarchal inner voice admonished her not to waver, not to allow it. What “it” was, she could not say exactly—his mastery over that simpering girlish element that floated in her psyche.

After five months of ecstatic coupling, he sat Diane down for a lecture, handing her a to-do list to correct bad habits. Bieler’s broth and raw vegetables would purge her body of poisons. She should attend a past-life regression group to erase her old Roman Catholic negative tapes. Daily meditation was crucial to calm her chaotic energy that was disturbing his hard-won serenity. A trip together to Maui was on the agenda, a test of her willingness to change.

A child of the midwestern prairie, Diane had always loathed islands, especially those of the paradise variety. They resembled cages, their inhabitants unable to escape, and running endlessly in one place, like pet hamsters on toy Ferris wheels. Her light complexion was allergic to tropical sun. She was wary of scraping herself on coral and unnerved by translucent jellyfish that floated in the surf.

“It’s beautiful there. The sea, the breezes, the sun. It’s close to nature, close to Spirit,” Mark said.

Mark’s concepts fascinated Diane, but their heretical oddity alarmed her. This “Spirit” he constantly invoked seemed to have little to do with her idea of the Christian Holy Spirit, a sweet white dove that fluttered overhead and radiated featherweight grace to any soul who prayed. She thought Mark’s Spirit sounded like a black broody hen squatting intrusively over the entire universe, with no boundary between its heavy belly and the soul-eggs squashed beneath it.

The threat was implicit. Accompany him to Maui, or else.

His travel agent booked a seven-night package, a bargain consolidator rate for a two-bedroom condominium with ocean views, the quintessential Biblical span in which to seal their perfect union in a Maui Garden of Eden. Diane suggested going Dutch, and Mark didn’t object. She flinched as she wrote the check, a huge dent in the emergency fund she had cobbled together from her modest salary as an administrative assistant at a national accounting firm in a fifty-story downtown high-rise.

In late June, a week before departure, she telephoned her childhood friend Angela to talk about the travel plans. The two women seldom got together, but they touched base every few months. They had played wild horses in the empty lots choked with weeds, behind the new suburban tract houses that had cropped up near their Glenvale, Illinois subdivision. In the springtime tadpoles hatched in the mud puddles, and in winter the girls skated on the ice patches that dotted the fields. Through serendipitous twists and turns, Angela lived less than a mile from Diane. She was a successful academic, a tenured professor at Loyola Marymount, an expert in nineteenth-century British literature, whose husband, also a professor, had been killed in an automobile accident seven years earlier. Diane and Angela had taken separate paths in life. But there was always the shorthand of those wild horses.

Diane gushed her

delight, painting Maui in gaudy colors like a Gauguin Tahitian landscape. But her voice had an undercurrent of doubt, perhaps even a smidgen of panic.

“I thought you didn’t like the tropics.”

“I don’t normally, but this is different. With Mark, I’ll learn so much. He’s been a bunch of times, and knows a lot of people, he’s a superstar in the New Age world.”

There was a silence on the line. Then Angela said, “I’m not being critical, but are you sure this guy’s right for you? I only met him briefly that one time, and I didn’t say anything, but now I’ll tell you straight out—he doesn’t seem like a nice man.”

Diane said, “I’ll be careful. I can’t back out now. Anyway, I want to make it work. It’s exciting, he’s so much more interesting than all the other guys I’ve dated.” She promised to send Angela a postcard.

At the Maui airport they picked up a bright blue Neon rental car. Mark commandeered the wheel, and sped them twenty miles to the condominium complex, a hodgepodge of thin-walled concrete and stucco structures resembling gigantic half-assembled Legos. It was late afternoon, near twilight. There was no elevator, so they each lugged suitcases up a flight of concrete stairs to their unit. A violet expanse of ocean was barely visible from a sliding glass door that led to a rough concrete patio fenced with a flimsy stainless steel railing. Mark was insistent that they walk immediately to the ocean. Diane felt uneasy. Her strict father had trained her to first unpack and organize her belongings when arriving at any new place. She said nothing. Already she was counting the days until their return flight.

They walked through the complex, past scraggly palm trees drooping in concrete planters, out a rusty wrought iron gate, and across the highway to a narrow strip of pebbly beach. Mark pointed to the sunset as if it were his own creation.

Diane agreed. “It’s nice.” She did not say that the sky’s dull russet color lacked the flair of Turner’s palette of coquelicot and Indian yellow. It had been expensive to come all this way, and the reality of this storied island should not only match, but indeed should surpass the effects of mere daubed pigments, even those achieved by genius painters. Apparently her money was wasted. She wanted to turn around and go home. They ate dinner at a vegetarian restaurant in a strip mall a half-mile away, and split the check. Sleep was sound that first evening, as the journey had tired them out.

The next day they lazed about, Diane absorbed in Bleak House, as she was on a Dickens kick. She was irritated by a character who frequently referred to himself in the third person when he spoke: “The butterflies are free. Mankind will surely not deny to Harold Skimpole what it concedes to the butterflies.” Somehow, he reminded her of Mark. She pushed down this thought. Ridiculous to compare an exaggerated Victorian villain to the real life Mark, who rode herd on his pager and talked nonstop on the condo telephone with mysterious contacts who shared his passion for holistic knowledge.

Mark’s food discipline was strict: all organics. In the early morning he had sent her out to an organic food market three miles away. His precise list included two dozen eggs and enough sprouted grain bread and fruit to make breakfasts the entire week, and also lunch food for a day trip he was planning for tomorrow. The cost of all this upset her, almost twice that of the Vons where she shopped in Los Angeles, more expensive even than the upscale Gelson’s she avoided. At his request she also purchased, for an exorbitant price at a nearby convenience store, a small Coleman cooler and blue ice, items which they would have to leave behind when they returned home. She had charged a total of $220 on her Visa, as he said it would be too complicated to use two credit cards.

He didn’t mention reimbursing her, and she was afraid to bring it up because she feared the label of a nitpicky cheapskate, and that he would point out her “money issues.” She could only hope he voluntarily would square the account later, though she suspected he would conveniently forget. At sunset, they walked on the beach, ate at the vegetarian restaurant, and split the check—already “our” place, said Mark, though Diane secretly longed for a green salad tossed with white meat chicken chunks, and had made a mental note of both a Baskin Robbins and a hamburger place, neighbor tenants in the strip mall.

On the third day, in midmorning, they departed on an excursion, the destination a surprise. Mark stated that one other person would be joining them. To add a little sex appeal, Diane donned a skimpy tee and a beribboned straw sunhat, but the rest of her outfit was practical, loose-fitting hiking capris and running shoes. Mark wore a pineapple-pattern Hawaiian silk shirt, slim black jeans, and Doc Martens boots, gold shimmering around his neck and wrists. They threw light coats in the back seat, Diane a nylon windbreaker, Mark an Italian leather jacket. Diane had made and packed into the cooler a picnic lunch, three turkey breast sandwiches on a sprouted grain flourless bread, a stash of raw carrots and celery, six apples and the same number of energy bars, three raw peanut-butter coconut cookies, and also six bottles of Geyser spring water and unfiltered pomegranate juice.

Mark drove the Neon five miles inland, to a trailer parked in the red clay earth next to a sugar cane field. Cicadas trilled an earsplitting plainsong. A stout native Hawaiian woman dressed in a lime green cotton overshirt and black shorts opened the trailer door. Inside, a middle aged man and two long-haired tattooed adolescent boys hunkered in a dark room paneled in fake wood, staring at the flicker of the television, where Vanna White was spinning the Wheel of Fortune.

The woman grinned with white, gapped teeth, and encased first Mark and then Diane in mama-bear hugs. Her multisyllabic native name beginning in K and ending in A was unintelligible to an American ear, but she called herself Kate for the benefit of tourists.

Mark turned to Diane. “Kate is a priestess in the old religion. She’s connected to Spirit. She’s our guide today.”

Okay, thought Diane, this should be a memorable adventure. Mark’s labyrinthine network astonished and intrigued her. The trio set out, Mark at the wheel, Diane paging through her Fodor’s guidebook in the front seat, Kate sprawled over half the back seat. The radio was off, and the three were silent, taking in the primordial wild-scape, remarking on the occasional flash of flocks of red or yellow birds. Once they spotted a huge tubular brown rodent.

“Ah, a mongoose,” Kate said.

“Rikki Tikki Tavi,” Diane said, and when there was no response, “You know, that brave mongoose character in Kipling, he’s a pet, and he saves his human family from cobras.”

Mark said, “Those old imperialist tapes, I would never let a child anywhere near Kipling.”

After a half hour, Kate motioned toward an unmarked paved road that wound up a hillside. At the summit was a field of black pumice rubble. Each stone was about one foot in diameter, pockmarked with white and orange lichen. Kate pointed out square structures three feet high constructed from the stones. It was here, on these altars, she intoned, that healing rituals were performed by the ancestors.

Diane walked up to an altar, boosted her body up, and sat on the top. On one side, the ocean waters sparkled turquoise and lapis blue. On the other side, in the far distance, stood a range of emerald mountains. Rainforest clouds covered their peaks. In the near view, between two cement buildings, was a brown clay lot. A high chain link fence enclosed the lot, behind which two mastiffs paced back and forth. Diane shuddered. She sensed what Kate left unsaid, that captive slaves had been sacrificed here, that their angry spirits hovered over the site.

Diane started back toward the car. Kate walked by her side and unexpectedly put an arm around her shoulders. Startled, Diane drew back.

Kate said, “Don’t be scared, everything’s OK, I won’t let anything bad happen.”

Diane said, “I’m not scared, I’m just a little jumpy. Must be jet lag.”

Mark had been walking a little ahead, and turned around frowning. “It’s not jet lag, there’s not enough of a time difference.”

“That’s true,” said Diane. “I don’t know why, but I’m a little off-balance. Anyway, Kat

e, thank you for showing us around. This scenery is spectacular, like a lost kingdom in a fairy tale.”

They continued for two hours on the road that meandered by the coast, snacking on energy bars, stopping several times at basalt outcroppings on beaches of pebbly sand. All the sites were unexcavated, not described in the guidebook.

“Why aren’t these places documented?” Diane finally asked, exasperated. Kate was vague. These were holy places, sacred to the gods and never disclosed to outsiders.

Mark commented that the silly guidebooks written by westerners were all wrong. “They’re trapped inside their own heads, and they simply don’t get it,” he said. Whenever he invoked the “it” Diane never dared ask him to explain exactly what he meant. His tone somehow replicated her father’s: it’s my way, or some treacherous highway.

In mid-afternoon, they reached a volcanic formation next to the ocean. Two hundred years ago, an earth-god had extruded hot molten lava, which cooled and molded into an undulating black and gray moonscape. The road crossed over a solid black lava bed. To their left, the land-side, lay a gigantic black lava field, to their right, toward the ocean, the lava disappeared beneath breaking waves. Wind and water had created a pebbly beach that stretched in both directions along the surf.

Mark parked the Neon on the lava bed. The air was sweltering, even with the ocean breeze, the black stone absorbing the heat from a fierce sun in a cloudless sky. Kate opened the trunk and removed two papayas wrapped in broad flat leaves. She chanted a tuneless abracadabra, and gave one to each of them. Her instructions were to lay the papayas on the ground as offerings, after first whispering prayers. Mark grabbed his papaya, and sprinted away, toward the ocean.

What a farce, Diane thought. She picked up the papaya to play out her assigned role. Turning away from the ocean, she crossed the road, and hopping from slab to slab of the black lava for several hundred feet, she found a crevice, sat down, and placing the papaya inside, raised her palms in blessing.

Curious Affairs

Curious Affairs